Respecting the Season

Reflecting on losing in a major jiu-jitsu competition and what really got lost along the way

Long time, no see, Substack subscribers! Welcome, friends from my ConvertKit list. It’s been a while since you’ve all heard from me and you’re about to read more about why. I’m sorry to have left you hanging for this long.

This piece returns to my favorite kind of writing: the longform personal narrative essay. I hope this story “leads by example,” and in reading it, that it might inspire you toward more self-reflection, self-understanding, and deeper about your own life and what you make of it.

If you liked this post or know someone else who might benefit from it, please share it.

A month ago, I found myself at a group dinner celebrating a training partner’s birthday. The dinner was at a Thai restaurant, but for some reason the meal concluded with fortune cookies accompanying our checks.

I was less hungry for Thai food that night than I was for some sign from the universe that I would do well in a major jiu-jitsu tournament in seventeen days’ time. I cracked the cookie in half, craving some good omen inside of it, some positive nod from the universe for my performance in the weeks to come.

Instead, the cookie gave me this, something that could not be fashioned or related to a tournament outcome no matter how hard I tried to reinterpret the message:

“This year, your highest priority will be your family.”

I sighed, put the fortune in my wallet, and spent the rest of the night—followed by the next seventeen days—trying to forget about it.

“After the tournament, it will be,” I reassured myself. “After the tournament…”

“After the tournament” was my personal refrain for the last twelve weeks.

After the tournament, I’ll stop the two-a-day training sessions at 6AM.

After the tournament, I’ll rehab everything that hurts. Head, shoulders, knees, and toes.

After the tournament, I’ll let myself relax a little.

If my last three months had been made into a Disney movie, “After the tournament” would be the opening song, the one where you meet the wide-eyed heroine before her world as she knows it gets rocked by the villain.

You might expect that the villain in this particular kind of story—less a Disney story than a combat sports story hinging around intensive preparation for a fight or series of fights—would be an opponent across the mat from me: the Apollo Creed to my Rocky Balboa or the Johnny Lawrence to my Daniel LaRusso.

I wasn’t until after the tournament in telling the story to myself—first to make sense of it, then to make peace with it—that I realized this:

The real villain of my own story was me.

One of the fundamental principles my first coach had imparted was that preparation for competition was about the “elimination of excuses.” Whatever things you didn’t want to do—whether it was the cardio work or the boring diet—were often the things that you needed to be doing as part of your preparation.

The goal was to approach game day knowing you had done everything possible to be at your best, to have no room for self-doubt when you shook the referee’s hand and bumped fists with your opponent across the mat.

I wouldn’t say I cut corners in the past when it came to competition, but in previous efforts to prepare, I could tell you exactly where there was more I could have done.

Competing at a new rank, at brown belt—the last belt below black belt—I felt like I had less room to leave things to chance. So for this tournament, I prioritized doing all the things I didn’t usually do but felt were important to improve my odds of success.

For the first time in my six-and-a-half years of training, I did everything I believed I needed to do and that would set me apart from the competition: I authoritatively built up my cardio. I scheduled biweekly drilling sessions focused on fixing specific aspects of my game. I scrutinized tape—both mine and my opponents’—to become as knowledgeable as possible about my own game and to have a point of view on my paths to victory when my game matched against theirs.

Over the course of the twelve weeks before the competition, I left no stones unturned, and had no “should have done’s” or “could have done’s” remaining. By the time I flew out to Las Vegas, Nevada for the biggest tournament of the year, I had taken the advice of “eliminating excuses” to heart, and I had every reason to believe that it would make me extremely successful.

My actual outcome could not have been more opposite from: instead of having my best performance yet, I had my worst performance ever.

I had eliminated all the excuses, but in addition to eliminating the excuses, I’d eliminated more than the excuses.

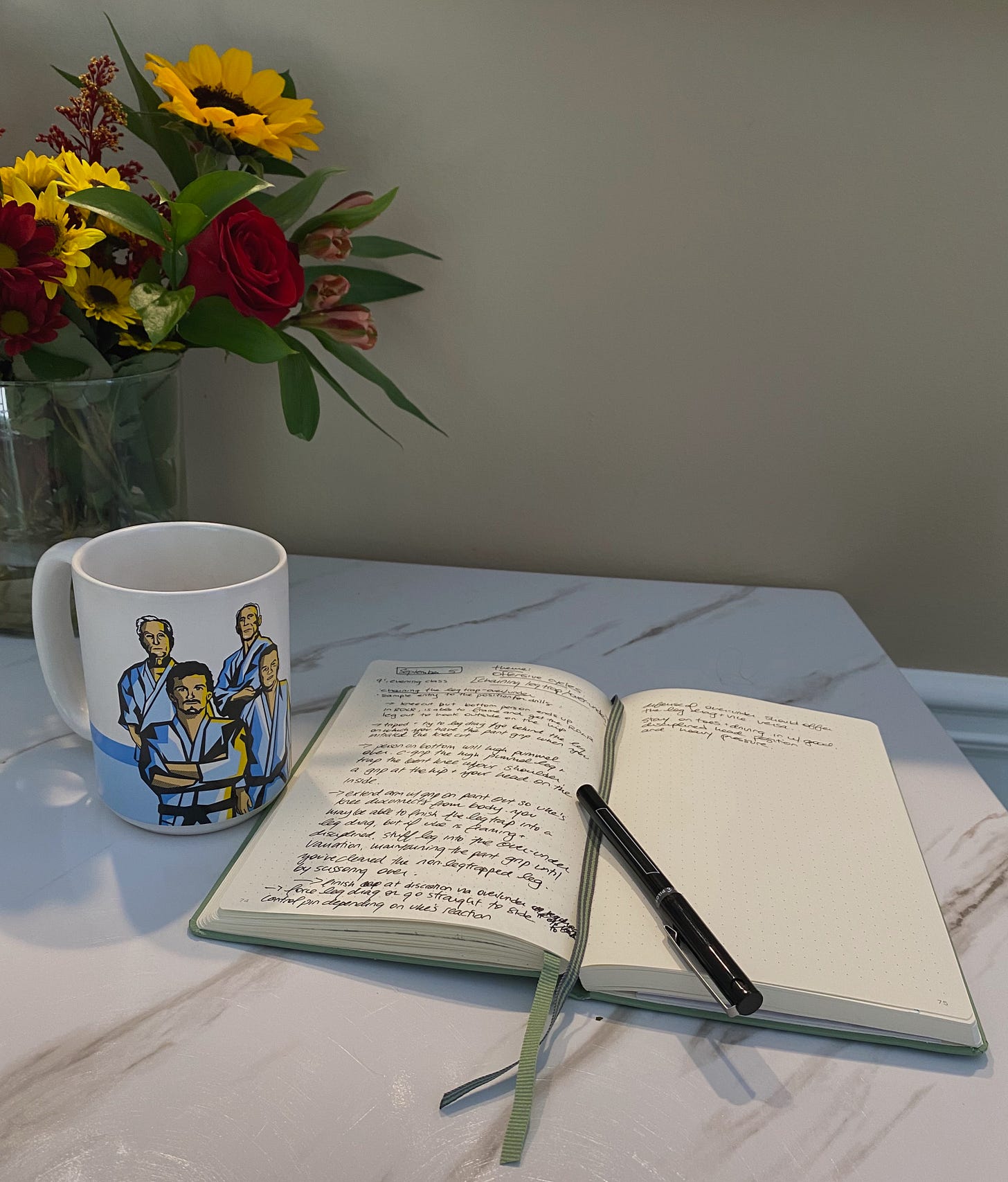

It wasn’t until the plane ride home that I started to realize what else I had eliminated along with the excuses, but the “writing on the wall” had shown up sooner: in text messages with certain friends, in pages of journals, in left-in-draft blog posts I thought I would share about my preparation before I decided against doing so.

When I read back my exchanges with friends and my notes to self, my commitment is palpable, but so is my obsession—to a fault and at my own expense. There’s also an undercurrent of desperation in journal entries that contain phrases like “let this be enough,” and “I can’t keep going on like this.” I’m wanting the whole thing to be over because I can no longer endure the pressure I’m putting on myself.

A “camp” isn’t supposed to be sustainable, but it’s clear that I can’t handle the pace at which I’m operating. My body is cracking under the weight of my physical efforts and my mind is cracking under the weight of my expectations: not just to perform well, but to win the whole thing and highlight reel everyone in the process.

Reading my own “receipts”, what really did me in were the events of the final week before the tournament: an injury flare-up has me reluctantly rushing to an orthopedist for a cortisone shot and a prescription for physical therapy. Unable to book the PT sooner, I get scheduled for a consult the day before I fly to Vegas.

The physical therapist manipulates the joint, assesses the severity of the ligament injury, and begins talking through a proposed course of treatment. The thing that breaks me in our session is not the pain from her prodding and not an exercise she makes me do. It’s an honest question.

“So what do you do for fun?”

I don’t have an answer.

Normally jiu-jitsu would have been the answer, followed by the standard Q&A that comes with telling someone who hasn’t ever done jiu-jitsu about what it’s like to train jiu-jitsu.

But that day I have nothing for her. As I deflect the question, I don’t even have an answer for it for myself. I look up to prevent the tears from flowing down my face, forcing them to settle back into my eyes. Like everything else in the camp, it’s an act of will and force. There’s no room for vulnerability, no time for tears. I refuse to break down in front of her, in front of an opponent, in front of my training partners, in front of anyone if I can help it

Along with the excuses, I’d eliminated the fun. I’d also eliminated a piece of my soul.

After the tournament, you can rest.

After the tournament, you can come undone.

After the tournament, you can be human again.

The night before the tournament, I had no appetite—a rarity. The day of the tournament, I had been up on the hour every hour since 2:30AM. Using the bathroom. Visualizing opening sequences. Trying to go back to sleep.

I’m always nervous when competing, but never had a physical reaction quite like this. Every thought from my brain to my body—to calm down, to recenter, to trust and believe in myself and perform in a few hours’ time—seemed broken, the usual code corrupted.

My first match, I eked out a victory in spite of some bad unforced errors. My coach was frustrated. I was more frustrated. I was still in the bracket, but couldn’t get over the feeling that the win felt like a loss.

My fiancé came over to the holding area ahead, trying to comfort me and put me back together ahead of the next one,

“People will look at that tape and see that she made me look mortal,” I told him.

“But Erica…you are mortal.”1

The biggest irony is that letting myself be human—and embracing it—could have made all the difference.

For those three months spent in camp, I wish I’d had the courage to be honest with myself and others when I wasn’t doing well. Those moments of vulnerability could have become moments for solidarity and much-needed support.

A few breakdowns in the locker room, or even on the mat—embarrassing as it can be—would have served me better than remaining hellbent on keeping a brave, invincible front run front of others. The truth was that the stronger I pretended to be, the more brittle I actually was.

If I’d permitted myself more human moments, I might have taken my preparation in stride, pushing myself close to the breaking point but not past it. I might have been more resilient after the first lackluster match, and been able to bounce back to come out stronger in the second. I might have won that match and gone on to win the whole thing.

Instead of permitting myself the human moments, I spent the camp turning myself into a machine, only to rust and break down in the moment when my performance mattered most.

I went on to Iose my second match. I hardly remember being in it. My preparation did not translate into action. My body was there but none of me was present.

My mind was gone. And once I lost, I realized my heart was gone, too

As I began grieving the loss and reminded myself of every feeling I’d had during the camp, I realized that I’d felt pretty much every emotion in the process except for love.

Somewhere along the line, in a desire to win—dominantly, perfectly, excellently—I had stopped training from a place of love.

This wasn’t the first time I’d lost love for jiu-jitsu. I’d gone through my share of love-hate moments with jiu-jitsu over the last six-and-a-half years. In those periods when I wasn’t loving jiu-jitsu, I persisted until I loved it again.

In the past, even in those period where I wasn’t loving jiu-jitsu, at least I had some emotion associated with jiu-jitsu. Even if they were negative emotions: negative fervor is still fervor. Fervor is feeling.

The most alarming part of the latest loveless period in my relationship with jiu-jitsu hasn’t been the usual stream of negative emotions: sadness, anger, fear, desperation, and pain. The most alarming part has been the lack of emotion at all.

As I’ve returned to train out of pure routine, desire for socialization, and maintenance of fitness, the hardest thing I am grappling with now is my own apathy, numbness, and indifference.

When you give something everything you have, one of two things happen:

1. It, fulfilling you, fills you back up.

2. It leaves you with nothing left.

To have committed myself as intensely and intently as I had to a goal only to fall short is one thing. Now, I feel nothing at all.

Hard work pays off, but overwork has its own price, too.

It’s now over a week since I came home from Las Vegas. The countdown to the tournament has been replaced by a countdown to a more mass-appeal, comprehensible, and more objectively significant milestones in a life: my wedding.

I’m in New York City in the basement of Kleinfeld’s, the Mecca of all things bridal, for my first dress fitting. It’s been months since I’ve paid attention to the appearance of my body in something other than a cotton kimono, or thought about it as something other than a means to some functional, competitive end.

There’s no time for self-consciousness as I strip down to nothing but underwear in front of a tiny Italian seamstress named Maria. She tells me to put on my shoes, a requirement for tailoring the length of the dress.

“Are you sure these are the ones you’re going to wear?” she says meaningfully. She can’t be more than five feet tall, and with a single, businesslike look, intimidates me more than any opponent I’ve had to grapple in the last year.

“Yes” I say, hoping I don’t rack up another foot injury before the wedding. The last few months of fractures and ligament sprains have made it an especially bad year for my feet in jiu-jitsu.

I bend over on a plastic stool, free my feet from my sneakers, and slip on the white heels. I fasten the buckles of the shoes and stand up with all the grace of a baby deer learning to walk. My feet look passably attractive for a change, the callused soles and bruised toenails hidden beneath the satin and crystal.

Maria unzips the dress and gives me another matter-of-fact look that says, “Now step into the dress.” I high step into the opening she’s made, careful not to catch the heel in the fabric between the front and the back of the dress. I’ve spent months in training rehearsing and making certain movements look fluid and graceful—but not these kinds of movements.

She zips me in and begins to prod at my frame, cinching and shaping the fabric into a true silhouette. In her all-black ensemble, as Maria revolves around me, she’s a gentle spider weaving a swift, skillful web of pins and clips.

She leaves only the slightest amount of wiggle room at the hips and waist, just enough to breathe and walk down an aisle. I’d spent the last two months worrying about being at a certain weight for competition. It dawns on me that I now need to concern myself with not gaining or losing too much of it so as to not waste the efforts of the fitting.

In thirty minutes, Maria finishes her first round of pins and adjustments. She pulls back the curtain for my mother to see the work.

I’ve never seen my mother happier—and as a categorically happy woman, this is a serious statement. I may not have won a gold medal a week ago, but today I look like an Academy Award trophy in shades of white, pearl, and silver.

My mom’s voice breaks with joy. My eyes soften. I figured I’d become someone’s wife one day, but I was never the kind of girl who fantasized about her wedding day or gave much thought to the pomp and circumstance of becoming a bride. If anything, I fought against it for fear of becoming a caricature.

This was what I had really been fighting off all summer: the logistics, the planning, the talk of guest lists and cake, all the stress and the expensiveness (in both time and money) of getting married.

I fought against it for fear of letting it consume me. I fought against it for fear it would weaken my focus and distract me too much from the competition.

But in this moment, I can believe in the magic of getting married. I can appreciate beautiful enormity and significance of the months to come.

Finally, I stop fighting it.

The fitting room is where “what ifs” pour in.

What if I had been more present for this process sooner?

What if I had let myself enjoy more of it along the way?

The questions were as true for the tournament as they were for the wedding. Whether I wanted to respect it or not, the fortune cookie was right.

“This year, your highest priority will be your family.”

The highest priority was not training and competing in jiu-jitsu, and it was never supposed to be. I forced it to be, fighting some deep down inner wisdom, that it couldn’t be.

I’d have performed better if I’d made peace with that truth before the camp. I’d have been happier along the way. I might have done a better job—both in the tournament and in the many things surround it—if I had acknowledged the fault line between my ambitions and my reality of this very particular year.

I wish I’d set the expectation of myself not to win, but to do my best at the competition in light of the many things competing for my attention rather than at the expense of them.

I wish I’d let myself get benevolently distracted by wedding activities because some of them were fun and indulging in them they might have kept the tournament in rightsized perspective.

In “eliminating excuses” ahead of competing, I eliminated precious opportunities that I could have relished ahead of the wedding: the family time that’s harder to come by now that I live out of state. The appointments to taste cakes and fawn over floral arrangements. The time for shameless indulgence in the vanity, drama, glamor, and absurdity that the wedding process brings up.

Roughly three thousand words later, it’s easy to see how I learned more from one loss than I have from any win, but if there’s one thing I take away from it, it’s a question to ask myself, one that transcends the tournament and the wedding and will carry me into whatever comes next with an intention of presence and in the spirit of fulfillment

What will it take for you to respect and embrace this season of your life?

I actually said this. Thinking back to it, it elicits a mix of cringe and compassion for myself.

Brave piece

Erica, you paint a rich picture of a competitor mindset. I practice “gina-Jitsu” and marvel at the technical plane you’ve achieved. I watched one of your matches during the worlds and it looked like a an exhausting battle of - grips and grit. And to be on bottom and keeping your calm! Keep it up and educating those not in the scene - but seek to be (ie, me!)