Interview: Livia Giles is Changing Her Angle

A Conversation with ADCC Veteran, Multi-sport Elite Athlete, and Business Owner on Motherhood, Transforming Identity, Redefining Success and more

Before we dig in, a quick bio of Livia Giles

Livia Giles is one of the most accomplished Black Belts out of Australia and half of one of jiu-jitsu’s most beloved “power couples”: her business partner and husband is renowned coach, competitor, and teacher, Lachlan Giles.

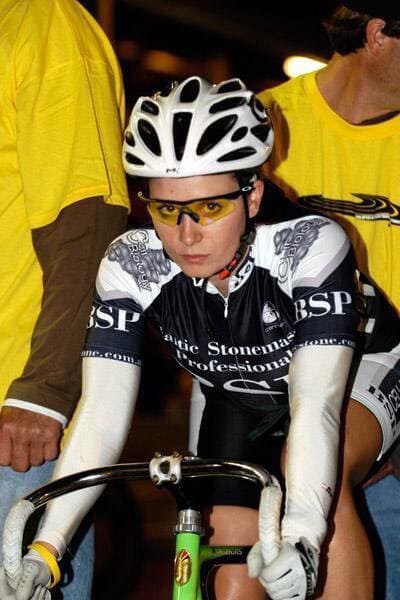

Prior to pursuing a lifestyle within and alongside the world of elite jiu-jitsu, Livia was an Olympic hopeful chasing success at the highest levels in other sports: first in gymnastics (from childhood until age 18), then in track cycling (for six years, into her mid-twenties).

Today, Livia is a mother to two adorable children (Walt and Audrey), is a coach and instructor at Absolute MMA St. Kilda, and is both business partner and camerawoman behind Submeta, one of the leading jiu-jitsu teaching platforms on the internet.

Without further ado, here’s a candid conversation with Livia Giles, which touches on her personal and professional evolution through various sports, through motherhood, and the ways in which she’s grappled with changes in her identity over time.

Introducing Livia Giles

Erica: Hi Liv! I'd love for you to introduce yourself and talk about your background a little bit, especially as we're speaking in 2025 and the last interview I found for you was a few years back. How would you describe yourself today?

Livia: Right now, I think my main role is a mom, but I guess I'm a lifetime athlete. I've recently—well, recently in the last probably three years—transitioned myself from being an elite competitor to not. So it's been a huge change in my life, more than I thought it would ever be.

My whole life, I've always been something else other than just an athlete, and that's always been really important to me. I have an education, I was a physiotherapist with my own clinic, and I had lots of other jobs going on. I guess I thought I had things to fall back on.

I've been involved in a few different sports in my life, so it's been a passion my entire life. But last year I turned 40, and after two kids, at some stage that high-performance stuff has a finish line. So it's been a real transition period for me in the last two or three years.

Right now I feel like I'm a jack of all trades. I've got two young kids, I'm a business partner in a gym, heavily involved withSubmeta [the instructional platform] with filming and editing, I'm coaching, and I'm just doing bits and pieces. I don't do everything super well right now, but that's where I'm at.

Livia’s Evolution of Athletic Identities: From Gymnast to Track Cyclist to Grappler

Erica: When you think about your first major transition—from gymnastics to track cycling—what was that like? Can you walk me through the different transition points in your athletic career?

Livia: I was probably 19 when I retired from gymnastics. The thing that really stuck with me was that my lifelong dream was to go to the Olympics, to be the best gymnast I could be. That never happened. I was probably never quite at that level, although I was very high level. Being one of the best in Australia in gymnastics doesn't place you anywhere in the world—you're still 50th or 80th in the world.

I was so desperate to do a different sport where I could be really successful. I remember asking my physiotherapist what sport my body would be suited to, and he said weightlifting, hammer throwing, or track cycling. This was back in the day when I didn't think weightlifting was cool, and hammer throwing—I'm five-foot-two, very short, so I don't know why he suggested that. In gymnastics it was all about being as small and skinny as possible, so I was a little horrified at those suggestions.

But I literally just turned up to a velodrome one day and said, "I'm doing cycling now, and I want to go to the Olympics"—which is insane because I hadn't ridden a bike properly since I was a young girl.

I did that for maybe six years with some success. I was doing well in Australia and Oceania, but in my early twenties I was studying for a degree and thinking, "Even if I did make it in cycling, I would need another five or six years of going really hard." Especially in track cycling, and especially for women, you just don't get any money for it. Even the women racing in the Tour de France now are basically on minimum wage.

That was a turning point—I was training my butt off, racing my butt off, spending all this money, and even if I did really well, I probably wouldn't be successful financially in the long run. That started to matter more as I was entering my mid-twenties.

I also lost passion for it along the way. So I decided to give up track cycling and focus on being a really good physiotherapist. I was studying physiotherapy and thought, "I'm going to go to the Olympics as a physiotherapist and still be involved in sports that way."

Because I'm quite obsessive, I thought “no more elite sport, no more racing.” I just got into this "must win" headspace. So of course I stopped cycling and went to a Muay Thai class with my brother.

I went to the Muay Thai class, but didn’t really understand Muay Thai or enjoy shadowboxing. The jiu-jitsu class that was going on at the same time looked more interesting to me.

At the same time, I met my now-husband,Lachlan. We worked for the same football team—I was a student physio, he was the physio. [Lachlan] was doing jiu-jitsu.

I thought, "Oh, that's what jiu-jitsu is. I should try it,” so I asked one other girl to try it with me. I was probably trying to impress [Lachlan], but it looked kind of fun. I thought, "I'm going to do it for fun. That's it. I'm going to keep fit."

Three months later, I did my first competition, went to Brazil for 6 weeks and did some BJJ there, and yep, now, here we are.

Erica: What year was that?

Livia: 2010 or 2011. End of 2010 or start of 2011.

Erica: Who were the big names in jiu-jitsu then?

Livia: Michelle Nicolini was my number one idol, along withCobrinha and Michael Langhi. Michelle was probably the biggest influence, and we ended up becoming really good friends actually. TheMendes brothers were just coming up—I think they were purple belts when I started, doing berimbolo. Everyone was like, "Oh, who's that?" But yeah, probably Langhi, Cobrinha, and Marcelo [Garcia] were the biggest names.

Livia on Coming up in Women's Jiu-Jitsu in Australia

Erica: When you were getting started, what was the culture like for female grapplers in Australia? I notice how many women are on the mats now in your gym, but was it always that way?

Livia: There were no women. Not to say there were literally no women—we had Sophia McDermott, who was Australia's first black belt, though she was living in the States. She came back and medaled at maybe brown or black belt no-gi, which was huge. We had Maryanne Mullahy, who still trains occasionally and is a great friend. When I first started, she might have just won Blue or Purple Belt Worlds, which was also a huge deal.

But when we opened Absolute MMA St. Kilda in 2014, there were no women at all. I had to tell the guys that I would open the door to the women's bathroom and there were guys peeing in there. I'd be like, "You can at least close the door.” It wasn't because they were trying to be unwelcoming. There just were no women, so they didn't have to think about it. The guys used to get changed in the middle of the mat because there were no women around.

At blue belt, I had to compete against men. I was always small, so it was rough. I remember a round robin tournament where I had four guys in my division. It's crazy—it wouldn't happen these days.

I started women's classes, and once I had four girls coming nearly every day, more and more started coming. But it was hard. Even though there were no women, I always had really good male training partners, and I've never had a really bad experience with men in jiu-jitsu. The creeps and really bad guys get filtered out pretty quickly in the academies I've trained with.

What we started doing in my early blue belt days was the higher-level guys—Lachlan, Kit Dale, and others—decided we all needed to get better. They started doing open mats and cross-training a lot more, because it was still a bit taboo back then. The girls got together and said, "We need to do that too. If we want to be good, we need to train with women." We started doing lots of open mats and cross-training.

My biggest breakthrough came because I kept fighting this girl called Lan Ta. She was like my nemesis at white and blue belt—she would always beat me. Then one year it was a referee's decision, and she still won, but I thought, "I'm a lot closer to her." That year she went on to win blue belt worlds, and I thought, "If she can do it, and I'm a referee's decision away from her, maybe I can do it."

The next year I won Blue Belt Worlds, then Purple, then Brown.

When I say there were no women, there were still some really significant role models in Australia—there were just fewer of us everywhere.

On Managing Career While Competing at the Highest Level

Erica: Tell me about the transition away from your physiotherapy practice and how that coincided with your athletic career.

Livia: That happened organically. I graduated physio in 2011 or 2012 and worked for private practices for a really long time. My big dream was to be a sports physio and help Olympic-level athletes, but it's a really tough job financially. Money was never a driver in my life, but it started to matter more in my mid-thirties. I didn't want to live on the poverty line and be an athlete forever—you can't.

I was thinking, "Am I going to see seventeen patients a day for the rest of my life, and if someone cancels, I don't get paid?" It's a fun job, but it's more of a part-time job financially.

When I say I've been a professional athlete, that's a lie. I never really got paid to compete or do much, apart from a couple hundred dollars for super fights back then. I always supported myself. I always worked, if not full-time then close to full-time, while managing to train twice a day plus weights—I think people can do a lot more than they think they can.

I ended up opening my own clinic at a gym, mainly seeing jiu-jitsu patients. I really enjoyed it, and I could make my schedule whatever I wanted to suit my training. I was actually working full-time until two weeks before ADCC. I was like, "I should take two weeks off to not work full-time."

The transition out of physiotherapy happened when we started Submeta. Lachlan was filming a lot of instructionals, mainly for Submeta and BJJ Fanatics, and every time we needed something filmed, we either had to hire someone external or I would have to cancel patients. I couldn't cancel patients last minute, so it started being financially not viable for me to be a physio.

At the same time, we were renovating our gym because we'd run out of space. We got rid of the physio studio to turn it into women's changing rooms, and we decided it would be better value for me to be the camera person for Submeta.

Then the pandemic happened, so our business was shut for nearly two years. During that time when we were shut, that's when Submeta really started. We filmed every day for a really long time and edited. By the time we reopened and launched the site, we were so far ahead that it would be very hard to copy now.

At this point, the business would have to go very badly for me to go back to physio. I've always wanted to have my own career, and until now it was always "I need something to fall back on if jiu-jitsu doesn't work out." Now with Submeta, I finally feel like I have my own thing.

I let my physio registration lapse this year for the first time. I was keeping up my accreditation, but I think it's time to move on. If I have to go back to physio, I'll probably have to study a bit more and get my credentials back, but I think this is the right decision for this time in my life.

On the Challenges of Transitioning Athletic Identity

Erica: You've talked about always being careful to maintain identity beyond just being an athlete. How has that concept evolved, especially with having children?

Livia: That's something I've struggled with quite a lot, actually. I think it stems from gymnastics and the external validation of it—being judged literally by judges, not just on how you perform but how you look, how you talk. Everything was like a show. Coupled with a pretty obsessive and competitive personality, I've always been like, "I can do everything and I can be the best at everything."

When I first started jiu-jitsu, I said I wasn't going to compete. Then I won Blue Belt Worlds and thought, "No one can ever take that away from me. That's enough." Then I thought, "Maybe I can win Purple and Brown and Black. Who's stopping me?"

I ended up winning Brown Belt Worlds and medaling at Black Belt no-gi, but the way I medaled wasn't by smashing everyone—it was by an advantage or something. I was like, "That feels like nothing."

For me, it was always like nothing was ever enough. Then we were talking about having kids, and I said, "I just want to make it to ADCC, and after ADCC I'll feel complete." I'd come second so many times at trials, then finally qualified for ADCC: biggest life goal realized. Then I got choked in the first round and thought, "I know I can do better. I'm better than that."

It was this cycle in my head where nothing was ever good enough.

Then I had Walt [in 2021], and I was desperate to compete again but also desperate to have another child. My sports psychologist said, "We're going to be back here having the same conversation in a year or two because that feeling will never go away. If you really want to have another kid, that's your answer."

I went back to him two or three times, and we kept having the same conversation. I just wasn't ready to admit it.

I ended up competing at the 2023 ADCC Trials, didn't win, had another kid in 2023, then had a knee reconstruction because I tore my ACL eight years ago. The knee was okay for a while, but it got to the point where I'd pull guard and my knee would just give way. I'd have a week off because it was swollen. I thought, "If I want to be on the mats for 10 or 20 years, I can't just pass on my knees and play half guard."

I guess where it left me—and it took me probably three years to accept—is that even if I trained the way I need to train to try to be the best in the world, I don't think I could be. I can hold my own against most women that do really well at Worlds or Pans my size, but I cannot hold my own against Adele [Fornarino], and she's pretty much my weight and she's the best. I can't do anything against her.

That was very different five years ago. Five years ago, I only fought to win gold. Now I don't think that I could, though I could possibly medal at Worlds if I had a great bracket. But for me to sacrifice the possibility of redoing my knee and being off the mat for another 10 months, the mental health aspect isn't worth it now. The time away from my kids because I'd have to train a lot, being so tired or hungry that it makes me a worse wife and worse mom, the time away from filming and working for Submeta, which is our livelihood: cost-benefit, it's probably not worth it anymore.

A lot of times at training I'll roll one or two rounds, then I'll film Lachlan rolling, and we put that up online. Obviously I'd have to take prep a lot more seriously if I were to compete.

I still miss it, and sometimes I roll really well and think I could do well [in competition]. But I have so many other things to consider that are bigger than that now.

Re-baselining Achievement and Training Goals in Motherhood

Erica: I imagine as a mother, the nature of individual athletic achievement has to look different. As someone who’s been so competitive and high-achieving for so long, where do you find success and fulfillment?

Livia: It's really hard for me. I've been seeing, for the first time in my life, a psychologist—not a sports psychologist, just a regular one. Being a mom has been really lonely at times, even though I have an amazing support network.

I have FOMO for the people at training, and I can't be there all the time. I hardly train at night because I'm home with my kids while Lachlan, as head coach, has to be there. We try to swap—I coach Friday nights and he stays home with the kids. I try to get a babysitter just for my mental health so I'm not stuck at home every night.

I think because I had kids a little later, I had this whole sense of identity and independence, and suddenly you have these two people who depend on you to live. I've had real issues feeling like I'm a success at anything.

People say bringing up kids is the most important thing in the world, and it is, but I still miss achievement. My personal achievement now is cleaning the house and making sure I don't have an anxiety attack because there's mess everywhere, teaching my kids how to self-regulate their emotions while I'm self-regulating mine—because no one ever taught me that. My self-regulation used to be choking people at jiu-jitsu.

My professional achievements have taken a backseat because it's really hard to do it all when you're a mom of two very young kids. Having time to sit down and edit—that's an achievement. Doing a good job coaching—that's a great achievement.

I'm definitely not as focused, and I'm a bit slack in training. I don't study as much as I used to, but I've had to change my focus in why I'm doing jiu-jitsu. I do it because I love the community, my friends are there, and there's a massive sense of connection through exercise and learning together.

I'm not getting ready to win anything, and that's been a huge shift. It's learning skill for the sake of learning skill now. I'm not going to fight to the death. I'm going to work on my escapes like any other person should. I've found a lot of joy in letting my ego go quite a bit.

Liv’s Concerns and Challenges in Modern Jiu-Jitsu Culture

Erica: What do you see as challenges for jiu-jitsu today, whether for women specifically or the sport in general?

Livia: I think it’s still the culture. We’ve got a pretty good culture where everyone feels welcome, and we have all sorts of people with minimal drama, but that’s not everywhere. The whole hierarchy and belt system—of course people should respect skill level, but that blind trust in someone and instructors abusing power just because they’re black belts is sick. For some reason that still happens. I can’t think of too many other sports where people pay to do the sport and get treated like that.

I also think we should just be allowed to train wherever we want. If people are paying for a service, just let them represent whoever they want and have that freedom. That’s my personal opinion. I understand different points of view and business decisions, but I think it creates this ownership of people and feeling of power, and then people abuse that.

Where the sport is heading with drug abuse (PEDs) is really disappointing. I’ve always been a pretty loud advocate for clean sport. I was drug tested since I was a little girl in gymnastics and cycling. Every time [Lachlan and I] speak about clean sport, it’s controversial. I think it’s insane that we have to do a “controversial post” about clean sport.

The argument we get is, “Well, it’s not banned.” Well, it is in IBJJF, maybe not ADCC. But also, I don’t want to do it because I think it’s cheating. There are big health risks, especially for women with fertility. I don’t want to take human growth hormone or anything else just because everyone else is doing it.

I think it’s completely wrong and sets a really bad example to the younger generation that you have to dope to achieve something. You don’t. There are quite a few people that are completely clean. I know 100% that Lachlan has always been clean. We’ve done random drug tests on people like Adele, Lucas [Kanard], Levi [Jones-Leary], and they were completely clean. They’ve been big advocates for clean sport, and their results have been outstanding.

It’s possible, and not everyone dopes, but the people that do are convinced that everyone else does. It’s really sad.

The Evolution of Identity and Success

Erica: Looking back on this transition, what’s been the most surprising thing about letting go of elite competition?

Livia: The hardest thing for me has been accepting how much of my self-identity was being an athlete and being relevant in the sport. I worked so hard on being a physio, being educated, being smart, having all these other things. When the competitive jiu-jitsu got taken away—when I decided not to do it—I had no idea who I was, and it really took me by surprise.

There’s a majority of blue belts in my club who don’t even know I’ve competed. They might see a highlight somewhere and be like, “Oh wow, you competed.”

That was hard for me, but not everyone’s like that. I have plenty of friends who were high-level [in jiu-jitsu] and they were like, “Yep, I got out what I needed and I’m just in a different phase of my life,” and they didn’t think twice about it.

I think it’s my personal journey of how much I tied myself to being this athlete. It is me, but I’m all these other things as well. I just never thought it would be so hard to let that go.

Finding New Fulfillment and Perspective

Erica: Where would you say find fulfillment now, especially as life has have changed so dramatically?

Livia: What I’ve really been enjoying is being a really good teammate and trying to be a really good training partner for Adele, Brianna [Ste-Marie], Nadia [Frankland], Alanis [Santiago]—whoever is getting ready for competitions. I’m trying to be the biggest cheerleader. I’m there every day, and if someone needs a hard round, I’ll give it my 100% even though it might not be as much resistance to them. But I’m always trying to be consistent—I’m here and I will be the best teammate I can be, because other people have done that for me when I was trying to win Worlds.

I get a lot of joy out of that now, and it’s a different kind of joy. I miss the feeling of winning—it’s the most selfish, best feeling in the world, and I’ll miss that forever because I don’t know if I’ll get it back from anywhere else. But seeing your teammates and people you really love do so well makes me cry. It’s the best feeling in the world, and it’s nice to be a part of that, however small my part is.

The way I train has really changed too. It’s learning skill for the sake of learning skill now. If my knees are messed up and I can’t do butterfly hooks, I get passed, and then I get joy in trying to get out of side control because I never really worked on that before. I didn’t let anyone pass my guard ever because I was like, “No woman will pass my guard.”

Now they do, and I’m not going to fight to the death. I’m going to work on my escapes like any other person should. I’ve found a lot of joy in letting my ego go quite a bit.

I’m trying to be the best mom, trying to be a better wife, trying to be better at editing and contributing to Submeta and the jiu-jitsu community. It’s been a massive shift away from constantly trying to be the best at something, but I’m still trying to be the best—just at different things now.

And you know what? That’s okay. It’s actually pretty great.

Want to stay in touch with Livia Giles?

If you want to follow Livia, here's a link to her Instagram.

If you find yourself in the Melbourne area, you can visit the gym where Liv trains and coaches: Absolute MMA St. Kilda.

If you want to check out Submeta, the leading jiu-jitsu instructional platform she runs with her husband Lachlan Giles, you can visit submeta.io.

You made it to the end. Thanks for reading!

If you're a longtime subscriber, thanks for being here.

If you're new to this Substack and enjoyed this conversation with Livia Giles, please share this post or drop a comment. I'd love to know what you thought about the piece.

If you like the spirit of what you see and are down for the ride of what comes next, consider subscribing for free at the link below.

See you next time,

EZ